Spring Frosts Across Türkiye: A Warning from a Disrupted Climate System

The frost events experienced across Türkiye this spring were not merely a meteorological surprise — they were a warning sign of a deeper disruption unfolding within the climate system. At a time when trees had already blossomed, fields had been planted, and farmers had planned their harvests, a single night of frost wiped out an entire year’s labor in some regions and permanently damaged trees that had taken decades to grow. Behind this event lies a complex process that leads many to ask: How can such intense cold still occur in an age of global warming?

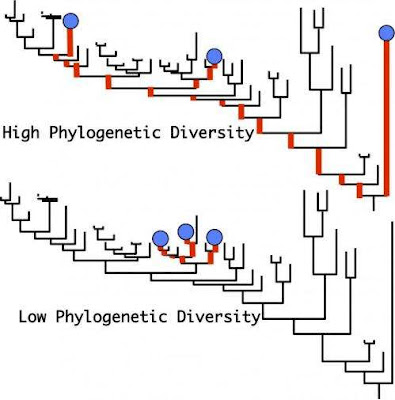

The polar vortex is a massive ring of cold air circulating in the upper atmosphere around the Arctic, roughly 10 to 50 kilometers above the Earth’s surface. Under normal conditions, this vortex remains strong and confines cold air near the poles. In recent years, however, the system has weakened as the temperature difference between the equator and the poles has decreased.

The polar regions are warming at more than twice the global average. As Arctic sea ice melts, the reflective white surfaces that once bounced solar radiation back into space are replaced by darker ocean waters that absorb more heat. This accelerates Arctic warming even further.

As a result, the temperature gradient that drives atmospheric circulation weakens. Jet streams — the high-altitude wind corridors — begin to meander and destabilize, disrupting the balance of the polar vortex. Cold air masses that were once trapped near the poles can now more easily spill southward, reaching regions as far as the Eastern Mediterranean.

As the planet warms, some regions will paradoxically experience colder conditions at certain times. While average global temperatures rise, atmospheric instability increases. When the jet stream bends and stalls, one area may experience record-breaking warmth while another sees polar air plunge southward — sometimes even bringing snow to places like Arabia.

The spring frost event in Türkiye was a direct result of this dynamic. In late March and early April, a polar-origin air mass traveled southward through the Balkans, pushing nighttime temperatures in Central Anatolia and the Western Black Sea region unexpectedly below freezing. Temperatures fell 10–12°C below seasonal averages, causing severe damage to early-blooming crops such as apricots, apples, and hazelnuts.

Public discussion of climate change still tends to focus almost exclusively on rising temperatures. Yet this represents only one side of the system. The real issue lies in the disruption of temperature gradients, seasonal rhythms, humidity patterns, and wind circulation.

Today, Türkiye faces both prolonged summer droughts and increasingly frequent spring frosts — two phenomena rooted in the same cause: atmospheric imbalance. Global warming no longer simply makes summers hotter; it also makes springs far more unpredictable. For farmers, this means not knowing when to plant, being unable to anticipate flowering periods, and living with uncertainties that often fall outside insurance coverage.

Türkiye’s agricultural production remains largely dependent on open-air conditions. With the exception of greenhouse farming, production relies on predictable seasons. That foundation is now cracking — and even greenhouses are increasingly affected.

This spring, apricot and apple producers in provinces such as Malatya and Isparta suffered losses of up to 60 percent due to early April frost events. Although agricultural insurance systems partially cover frost risk, damage assessments and compensation processes are lengthy and complex. Small-scale farmers are often unable to recover from these losses.

According to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute, annual fluctuations in fruit production caused by spring frost have reached up to 30 percent over the past decade. This translates directly into food price instability and income uncertainty in rural areas.

Such events are no longer exceptions — they are becoming the new normal. As a result, agricultural policy, insurance systems, and even rural life itself must be rethought accordingly.

Early warning systems must be strengthened. The Meteorological Service’s regional frost-risk forecasts should be delivered to farmers instantly through mobile-based alert systems. Warnings published only on official websites are no longer sufficient. During major frost events, all media outlets should actively broadcast urgent alerts: “Frost is coming — take immediate action.”

Agricultural insurance reform is also essential. As frost risks become harder to predict, climate-based insurance models must be adopted. Insurance systems should have a say in determining where and when certain crops are planted.

Crop selection and genetic resilience matter as well. Late-blooming varieties should be encouraged in frost-prone regions. More importantly, crops planted outside suitable climatic conditions may need to be excluded from subsidy and insurance coverage altogether.

Field-level management practices — such as windbreaks, microclimate design, and frost fans — must become more widespread, supported by targeted financial incentives.

This year’s frost may have been among the most severe in recent memory, but it should also be seen as the beginning of a new climatic reality. The weakening of the polar vortex and the southward intrusion of cold air masses reaching Türkiye are clear warning signals. Climate change is warming the poles — while freezing our springs.

If we continue to view these events merely as “unlucky weather,” both farmers’ livelihoods and the long-term stability of our food systems will continue to erode. The challenge is no longer only about stopping warming; it is about managing instability and adapting to a climate that has lost its balance. Because global warming is no longer just changing temperatures — it is reshaping the entire climate system.

Comments

Post a Comment